In 1840, Texas Ranger Captain Jack Hays and twenty of his men tracked down two hundred Comanches herding stolen horses.

Hays said, “Yonder are the Indians, boys, and yonder are our horses. The Indians are pretty strong. But we can whip them. What do you say?”

The Rangers charged, killed the Comanche leader and the rest of the warriors ran.

That’s a typical Ranger story.

The nineteenth century Texas Rangers were special to Texas and there’s a reason.

The Rangers were quick-shooting, hard-drinking, brutal, aggressive men, “just this side of brigands and desperados,” who fought a “war to the knife,” according to S.C. Gwynne, author of Empire of the Summer Moon.

In other words, they were just what Texas needed when the Comanche, Kiowa and Kickapoo were besieging us on every side.

The Rangers were also self-sacrificing.

Not only did they fight the tribes, they also fought Mexican soldiers (in two different wars), Mexican bandits and Anglo outlaws, while having to supply their own food, weapons, equipment and horses.

Rangers carried one rifle, two pistols, a knife and one blanket.

In time, Texas paid each ranger $30 per month.

Rangers also slept fully clothed in case they were forced to jump from their bedrolls and fight.

Texans organized the Rangers in 1835, and the new military waged all-out war against the tribes, especially during the 1839 Cherokee War in East Texas, the Council House Fight in San Antonio, in March 1840, and the (victorious) Battle of Plum Creek, against 1,000 Comanche warriors, in August 1840.

By 1841, the Rangers had undermined, if not broken, the tribes’ power. Comanches were still a threat, but the frontier was advancing west.

Things changed in 1861.

So many men left Texas during the Civil War, to fight for the Confederacy (including the Rangers), the tribes again ruled the plains.

Wilderness reclaimed whole parts of Texas because the Comanche had either killed the settlers or used fear and fire to push them out.

And the reconstruction government (1865-1870), did not allow the Rangers to operate, instead forcing a state police force down Texas’ throats.

State police were not effective against Comanche, and were highly unpopular–they were renowned for killing suspects without benefit of trial, particularly when those suspects were former Confederates.

By 1874, Texans were desperate for help against the Comanche and legislators again funded the Rangers.

Good move. The “Frontier Battalion,” about 450 men, fought in fifteen Indian battles.

After U.S. Fourth Cavalry Commander Ranald Mackenzie and his troopers, and the Rangers, were through with the Comanche, the tribe agreed to remain on the Fort Sill, Oklahoma, reservation.

The Rangers also “thinned out” more than 3,000 Texas desperados, including bank robber Sam Bass and gunfighter John Wesley Hardin.

Rangers were also ordered to end several frontier feuds–which they did.

The Rangers have occasionally committed wrongs, as organizations are full of imperfect human beings.

Accusers have charged the Rangers with racial prejudice; of not always giving Hispanics and African-Americans the benefit of the doubt.

That probably happened.

A folk song originating in South Texas tells the story of Gregorio Cortez Lira, who killed a Texas sheriff.

The sheriff had it coming and Gregorio was brave, the song says, adding “Don’t run, you cowardly rangers, from just one Mexican.”

The history of the world is bathed in blood and injustice, and organizations usually mirror culture.

But the Rangers came through for Texas when Texas needed them, and I, for one, am grateful.

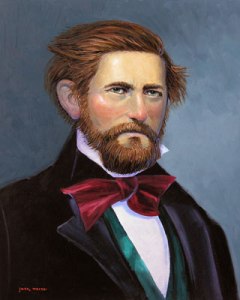

Jack Hays’ Statue in San Marcos

Jack Hays’ Statue in San Marcos

Click below to purchase one of Julia Robb’s page-turning historical Texas novels:

Julia Robb is the author of Scalp Mountain and Saint of the Burning Heart, eBooks for sale at amazon.com. She can be reached at juliarobb.com, juliarobbmar@aol.com, venturegalleries.com, goodreads, pinterest, twitter, Facebook, iamatexan.com and amazon author pages.

————————————————————–